Show Transcript

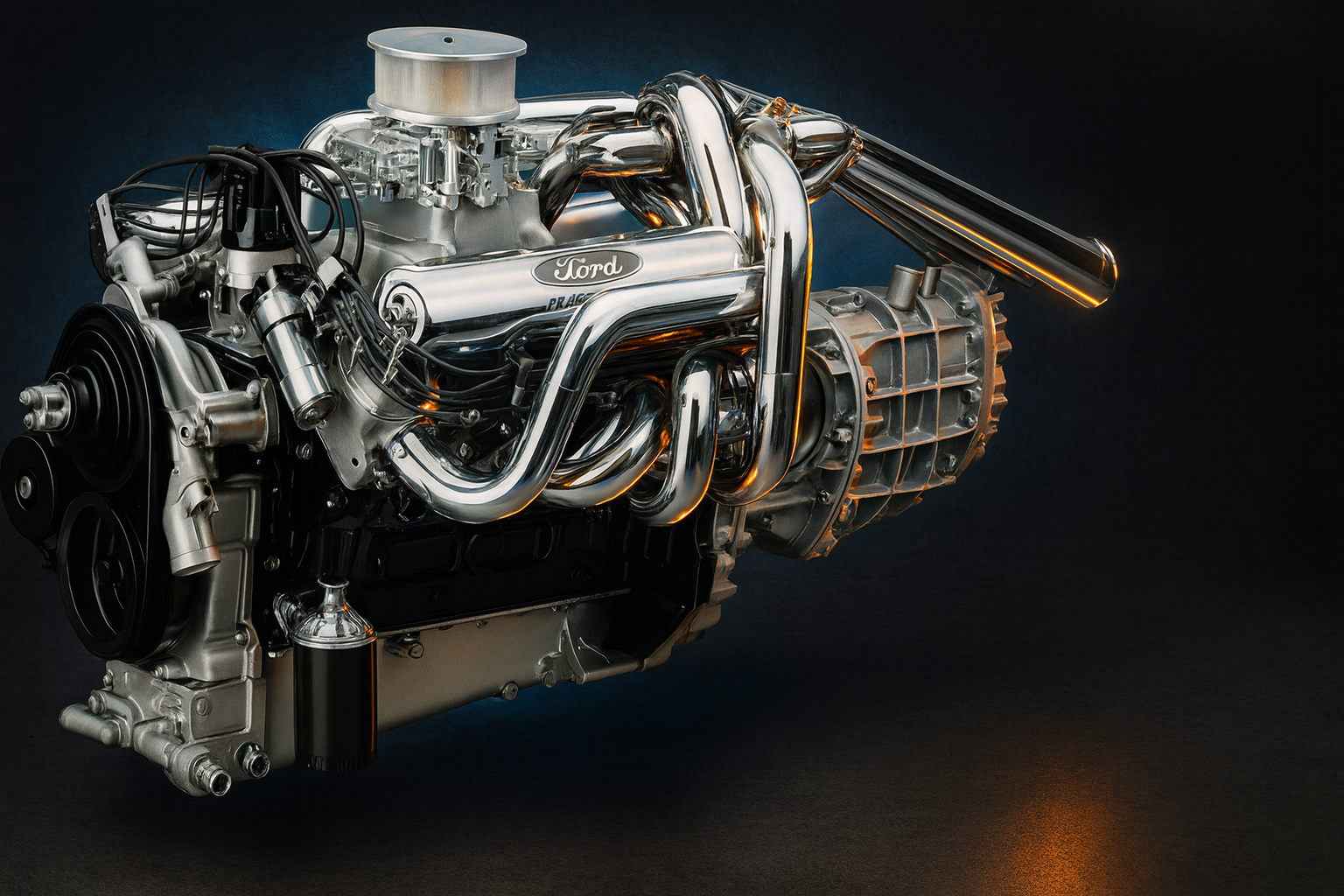

The Ford 427 Side Oiler: Racing’s Big Block Legend

Introduction: The Day Ford Declared War on Ferrari

he Ford 427 Side Oiler was the engine that took Ford from Detroit to victory at Le Mans… a race-bred big block built to beat Ferrari.

Ferrari thought they had endurance racing locked down. Six straight wins at Le Mans. A reputation that screamed perfection. Everyone figured nobody could touch them. Then along came Ford… ticked off, flush with cash, and determined to humiliate the prancing horse on its own turf.

They brought Carroll Shelby to the party, built a car called the GT40, and stuffed it with an American V8 so mean it would change racing history forever. That engine was the 427 cubic-inch FE Side Oiler, and it didn’t just beat Ferrari – it stomped them flat.

Now, Hollywood told that story in Ford v Ferrari, and sure, it’s a good flick. But the truth is even better and a lot more mechanical. The 427 wasn’t just a race motor pulled out of some secret lab; it was the peak evolution of Ford’s FE engine family, the same basic big-block line that powered F-Series trucks for years. Long before the Bullnose era ever rolled off the line, the 427 had already proven Ford could build a world-class engine out of production parts.

That’s what made it dangerous.

That’s what made it legendary.

And today, we’re tearing it apart, not with a wrench (though I’d love to), but with a deep dive into how this monster came to be, how it worked, and how it shaped the future of Ford’s big blocks.

Birth of the FE: The Foundation of Ford’s Big Block Era

Before the 427, before the GT40, and long before Le Mans glory, there was the FE: Ford’s first true big-block family. Introduced in 1958, the FE stood for Ford-Edsel, which sounds like a punchline if you only know Edsel as Ford’s biggest flop. But the FE outlived the car by decades and became one of the most important engine families Ford ever built.

Ford had a problem in the late ’50s: the old Y-block V8s were running out of headroom. They were fine for the smaller passenger cars and light-duty trucks, but Ford needed something that could scale… an engine that could handle both power and payload. The Lincoln and Mercury big-blocks were too heavy and expensive, so the engineers in Dearborn got to work on a new design that could do both jobs: go fast in a Thunderbird or pull a trailer in an F-Series.

The Engineering Vision

The FE was a masterpiece of compromise. It was big enough to move heavy cars and trucks, yet compact enough to fit under a standard hood. The block featured 4.63-inch bore spacing, which set a natural limit on displacement (that’s why you’ll never see an FE go much past 430 cubic inches). Later engines like the 429 and 460 used 4.90-inch spacing, giving them room to grow, but the FE’s tighter layout made it a stout, dense package.

Deck height was just over 10.17 inches, giving plenty of room for stroke without making the block excessively tall. Cast iron was the material of choice, not aluminum, which meant these things were heavy. They could be north of 600 pounds fully dressed. Engineers joked that lifting one was like bench-pressing an anvil with spark plugs.

The Deep-Skirt Block

One of the FE’s defining features was its deep-skirt block design. Unlike earlier engines that left the crankcase skirt short, the FE’s block extended well below the crank centerline, creating a solid cradle for the rotating assembly. This made it incredibly rigid, a trait that would later become crucial when Ford started chasing high-RPM endurance reliability.

The design had its quirks, though. For example, the intake manifold wasn’t just a cap sitting on the heads. On the FE, the manifold actually formed part of the cylinder head structure. That made for excellent rigidity and consistent sealing under load, but it also meant the intake was massive, sometimes tipping the scales at 70 pounds or more. Swapping one wasn’t a Saturday afternoon job unless you liked hernias.

Displacement and Applications

The FE family was flexible, covering everything from 332 cubic inches up to 428. The first version to hit the streets was the 352, launched in ’58. It quickly proved itself in both cars and trucks, leading to larger variants like the 360 and 390… engines that became staples of Ford pickups throughout the ’60s and early ’70s.

Those engines earned a reputation for torque and toughness. You could lug them all day on the farm, run them hard in a work truck, or drop one into a Galaxie and surprise the guy next to you at a stoplight. That’s the beauty of the FE design. It has same external block, but with different internals comes a completely different personality.

A Family Built to Adapt

The FE’s secret weapon was adaptability. It could idle smooth in a pickup or scream at 7,000 RPM in a NASCAR stocker. It was the Swiss Army knife of big blocks, and Ford took full advantage of that.

By the early ’60s, engineers started pushing it to its absolute limits. That’s when they discovered something crucial and the FE’s endurance Achilles heel.. the FE’s original oiling system wasn’t up to the job. The top-oiler layout fed the cam and valvetrain first, leaving the crankshaft last in line for lubrication. Fine for trucks. Not so fine for racing.

That flaw set the stage for the creation of one of the most famous racing engines of all time: the 427 Side Oiler.

Why Ford Built the 427

By the early 1960s, Ford had a problem. They were getting beat on the track, and badly. Ford was tired of losing. NASCAR and endurance racing had become more than just marketing. They were a battleground for engineering bragging rights. Chrysler had the 426 Hemi, GM had their own high-winding monsters, and Ford’s best effort, the 406 FE, was fast – but not fast enough. NASCAR had capped displacement at 427 cubic inches, which gave Ford a target. If they wanted to win, they had to hit that number and hit it hard.

The result was the 427 FE, an engine designed to dominate and survive at full throttle longer than anyone else. It used the same FE architecture, but everything about it was reworked for racing. Bore was punched out to 4.23 inches, stroke was set at 3.78, and the block was strengthened everywhere Ford could get away with it. Ford engineers had learned through painful experience that you couldn’t just bore and stroke your way to victory. High-RPM endurance killed engines through flex, heat, and oil starvation, so they went after all three. This wasn’t a warmed-over 390 anymore. It was a hand-built brute made to live at full throttle.

Strengthening the Block

The first step was casting integrity. Ford revised the FE block molds specifically for the 427, thickening the main webs, cylinder walls, and the oil pan rails. The engineers even modified the foundry’s core supports to reduce core shift during casting, which is something that had plagued earlier FE blocks and made cylinder wall thickness inconsistent. That kind of attention to detail was rare in production iron at the time.

The result was a high-nickel-content casting that could handle abuse far beyond what Ford’s standard passenger-car engines ever saw. Nickel made the iron harder and less prone to cracking under load, but it also made the blocks more expensive. Ford didn’t care. Racing budgets were generous, and this was war.

Next came reinforcement at the bottom end. The 427’s crankcase was a deep-skirt design like other FEs, but Ford took it further by adding cross-bolted main caps. Instead of the usual two vertical bolts per main, they added a pair of horizontal bolts that ran through the skirt of the block into each main cap, effectively tying the crankshaft to the block from both directions. It acted like a cradle that stopped cap walk… the tendency of the main caps to shift under load at high RPM.

To make this work, each cap had to be machined with precision flats and drilled passages for those side bolts. That added machine time and cost, but it created a bottom end that stayed tight and square at 7,000 RPM. Ford even extended the pan rails downward and added cast ribs between the bolt bosses to keep the block from twisting under load.

The Rotating Assembly

Inside, the crankshaft was a beast of its own. Ford used forged steel instead of the nodular iron found in lesser FE engines. It featured rolled fillets for stress relief and, in some racing versions, cross-drilled oil passages to improve flow between journals. These weren’t mass-produced cast cranks — they were hand-inspected and balanced for competition.

Connecting rods were shot-peened forged steel with 3/8-inch rod bolts, and the pistons were forged aluminum with full floating pins. Compression ratios ranged from around 10.5:1 on street versions to well over 12:1 in race trim. Combined with the short 3.78-inch stroke, the 427 was a rev-happy big block that could spin faster than most of its contemporaries without grenading.

Cylinder Walls and Cooling

Ford didn’t stop at the bottom end. They also beefed up the cylinder walls, which was critical for longevity. Earlier FE blocks could suffer from core shift that left thin walls on one side of a bore, leading to hot spots and eventual cracking. The 427 addressed this with revised core geometry and a thicker casting between cylinders.

The 427’s cooling passages were also reshaped to flow more evenly around the bores, especially in the upper water jacket. That helped even out thermal expansion, which in turn kept head gaskets intact under brutal conditions. The decks were machined flatter and truer than any production FE before them, which meant the heads sealed better and the engine could survive hours of sustained high heat.

Heads, Valves, and Flow

Although most of the 427’s legend lives in the block, the heads got attention too. Ford offered medium-rise and high-rise cylinder heads, each with larger ports and better flow characteristics than earlier FE designs. The high-rise heads used raised intake runners that improved airflow at high RPM, feeding the 427’s appetite for top-end power. Some later race engines even used tunnel-port heads with pushrods running through the intake ports — a bizarre but effective way to keep airflow high at extreme speeds.

To top it off, Ford developed lightweight cast-aluminum intakes for racing and even dual-quad setups that turned the engine bay into something that looked more at home on a drag strip than in a dealership lot.

All of these changes added up to a block that was as close to bulletproof as Ford could make it in the mid-’60s. Engineers used to joke that the 427 could take abuse that would scatter most other big blocks, and they weren’t far off.

Even so, the engineers knew there was one area that still wasn’t perfect: oiling. The FE’s top-oiler system was holding the whole thing back. The next step would be the innovation that truly separated the 427 from its predecessors: the side-oiler block.

The Oiling Problem

The FE had started life as a car and truck engine, not a race motor. Its top-oiler design fed oil to the camshaft and valvetrain first, with the crankshaft coming last. That was fine for your uncle’s pickup or your grandma’s Galaxie. At 3,000 RPM, it lived forever. At 7,000 RPM for hours on end, the crank bearings would start to go dry. When that happened, rods welded themselves to journals, and the engine went from thunder to shrapnel in a heartbeat.

Ford’s engineers couldn’t let that stand. They needed a fix that would feed the crank first every time, no matter how hard it was revved.

Enter the Side-Oiler

The side-oiler block was Ford’s answer. Instead of sending oil up through the center of the block and letting gravity do the rest, they created a dedicated oil gallery running down the side of the block. Oil came straight out of the pump and went directly into that gallery, which fed the main bearings first. Only after the crank had what it needed did oil get routed upward to the camshaft and valvetrain.

That simple change solved the FE’s biggest weakness. The crank, the heart of the engine, always had pressure, even under brutal loads. It turned the FE from a strong street motor into a legitimate endurance engine that could run flat-out for hours.

If you’ve ever seen a real side-oiler block, the difference is obvious. There’s a long horizontal bulge cast into the side of the block that houses the oil passage. It’s the giveaway collectors look for today, and it’s the reason those blocks are so valuable. They weren’t made in huge numbers, and the ones that survived decades of racing are prized like rare gold.

Why It Worked

What made the side-oiler design so effective wasn’t just the oil path. It was the whole system. Ford engineers balanced the galleries so that pressure stayed consistent from front to back. Each main bearing got its own direct feed instead of sharing a single passage. That meant less pressure drop, less heat, and much better bearing life at high RPM.

They also used cross-bolted main caps, which tied the bottom of the block together like a race cage for the crank. Each main cap was bolted vertically as usual, but also held in place with horizontal bolts running through the skirt of the block. That extra support kept the crank from flexing under stress, and when you’re spinning steel that fast, a few thousandths of movement can mean the difference between finishing a race and scattering parts down the back straight.

The combination of the side-oiler gallery and the cross-bolted mains gave the 427 incredible durability for its time. Engines that used to fail halfway through an event were suddenly living to see the checkered flag. In endurance racing, that was everything.

A Clever Workaround, Not the Future

It’s worth remembering that the side-oiler was a brilliant solution, but it was still a workaround. Ford was pushing the FE architecture past what it was designed for. Later engines like the 429 and 460 big blocks, and even the smaller Windsor family, went back to more conventional oiling paths, but with stronger main webs, larger journals, and better casting design from the start. They didn’t need a side gallery to survive because the whole block was built for it.

For racing, though, the side-oiler was magic. It was Ford’s way of saying, “We’ll fix it with engineering,” and it worked. The 427 side-oiler didn’t just solve a problem; it made Ford competitive again. From NASCAR ovals to the Mulsanne Straight at Le Mans, it gave Ford the endurance they’d been missing.

And if you want proof that it worked, all you have to do is look at the trophies.

The Racing Legacy of the 427 Side Oiler

Once Ford had the 427 Side Oiler dialed in, they didn’t waste any time turning it loose. NASCAR was the first proving ground. The short stroke, big bore, and bulletproof bottom end gave Ford the perfect combination for high RPM power and endurance. It could breathe deep, rev hard, and stay together under punishment that would turn most engines into scrap metal.

At a time when a 6,500 RPM redline was considered “aggressive,” the 427 was comfortably running past 7,000. Oil pressure stayed steady, bearings lived longer, and the engines came back from races still in one piece which, in motorsport, is the only statistic that really matters.

NASCAR Dominance

Ford teams quickly figured out that the 427 wasn’t just powerful, it was consistent. In NASCAR, consistency wins championships. The side-oiler setup meant the crankshaft got oil pressure first, and that allowed teams to run harder and leaner without worrying about oiling failures.

The 427-powered Galaxies and Fairlanes started showing up everywhere. Drivers like Fred Lorenzen, nicknamed “Fearless Freddy,” made Ford a serious threat. In the early to mid-1960s, he was running speeds that other teams simply couldn’t maintain without engine failures. That reliability came from the 427’s design. Those cross-bolted mains and the crank-fed oiling system did exactly what they were meant to do.

Other manufacturers were scrambling to keep up. The Chrysler Hemi had power, no doubt, but the 427 FE was a freight train that could keep pulling lap after lap. It didn’t care about being delicate. It was built for violence. It was just strong, simple American iron engineered to live.

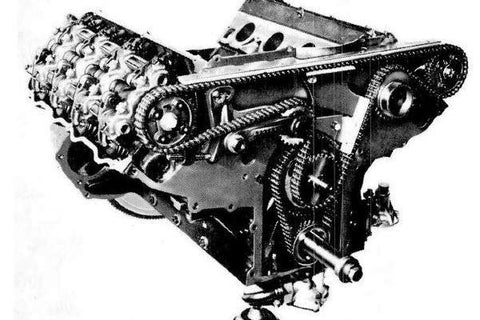

The Cammer: Ford’s Wild Experiment

Then Ford got ambitious… maybe too ambitious. In 1964, they unveiled a version of the 427 that made the racing world stop in its tracks: the 427 SOHC, better known as the Cammer.

The block underneath was still an FE, but the top end was completely new. Instead of the pushrod setup, Ford gave it single overhead cams on each bank, driven by a timing chain so long it could’ve come off a bicycle. The cammer heads breathed like crazy, with massive valves and hemispherical-style combustion chambers that looked suspiciously similar to what Chrysler was doing with their 426 Hemi.

The intent was simple: dominate NASCAR. The Cammer made a conservative 616 horsepower in “factory trim,” though that number was more for politics than truth. Tuned race versions easily pushed 700 horsepower or more. It was an absolute monster.

NASCAR, of course, took one look and banned it before it could ever dominate. The official excuse was that it wasn’t “production-based” enough. The real reason? It scared them. Nobody else had anything that could touch it.

Even though NASCAR shut the door, the Cammer found a second life on the drag strip. In Top Fuel and Funny Car, it became the engine that nobody wanted to line up against. Drivers like Connie Kalitta and Don “The Snake” Prudhomme made names for themselves running Cammers. You’d hear that shrieking, chain-driven top end echo through the pits, and everyone knew it was about to get serious.

In the quarter mile, Chrysler had the Hemi, but Ford’s Cammer was the one making tech inspectors sweat.

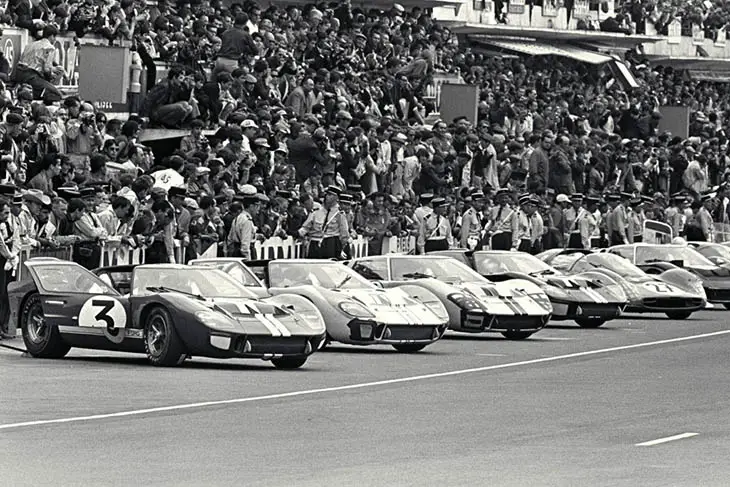

Le Mans: Beating Ferrari at Their Own Game

If NASCAR proved the 427’s durability, Le Mans cemented its legend.

When Ford first sent the GT40 overseas, it didn’t go well. The early 289-cubic-inch cars were fast but fragile. They couldn’t hold together long enough to challenge Ferrari’s dominance in endurance racing. That’s when Carroll Shelby stepped in. Shelby was the same guy who had already turned the British AC Cobra into a snake with an FE under the hood. Shelby knew exactly what the GT40 needed: the 427 Side Oiler.

The new GT40 Mk II was a different animal entirely. The 427 sat midship, low and angry, mated to a beefed-up transaxle to handle its torque. It was heavier, yes, but it was also unstoppable. Ford tested the hell out of it, often under the guidance of Ken Miles, the engineer-driver who pushed these engines to their limits.

Miles didn’t just drive; he broke things on purpose. He’d run engines at full load until they failed, then hand the remains to the engineers with notes on what went wrong. If the 427 survived Le Mans, it was because Ken Miles had already found every weak link during testing.

The Ultimate Show of Force

In 1966, Ford brought the hammer down. The GT40s finished 1-2-3, humiliating Ferrari in front of the world. It wasn’t a fluke, either. Ford came back and won four straight Le Mans victories from 1966 to 1969, and in 66 and 67 every one of those cars was powered by the FE family — the same 427 Side Oiler that started life as a production-based block you could, theoretically, buy in a Galaxie.

That’s what made it so impressive. Ferrari’s engines were delicate, hand-built art pieces. The 427 was a brute. It didn’t whisper; it shouted. It didn’t glide; it muscled its way down the Mulsanne Straight at over 200 miles per hour… in 1966. That’s mind-blowing performance for an iron-block V8 from Detroit.

And here’s the real kicker: those GT40 engines weren’t exotic prototypes. They were built from the same basic architecture as the 427 you could find on a Ford dealer’s option sheet if you knew which salesman to ask. They were blueprinted, balanced, and tuned to perfection, but at their core, they were FEs. Production blocks, racing glory.

The Ultimate Proof of Concept

What Ford proved with the 427 Side Oiler was that durability wins races. Power gets headlines, but reliability wins trophies. That philosophy carried through everything Ford built afterward. The 427 taught Ford engineers how to make big displacement engines live under stress. Lessons that filtered down into the 429 and 460 big blocks that powered the heavy-duty trucks of the ’70s and ’80s.

Every time one of those GT40s roared down the straight at Le Mans, it wasn’t just about beating Ferrari. It was about proving that American iron could take the best the world had to offer and come out on top. The 427 Side Oiler didn’t just win races; it changed Ford’s entire approach to engine building.

Why It Matters

If you’re standing in front of an ’80s Bullnose Ford, it’s easy to think the 427 Side Oiler doesn’t have much to do with your truck. After all, no F-Series ever rolled off the line with one under the hood, and even 460 big block only went in the F-250s and 350s of the time. But that’s the thing… the 460 exists because of the 427.

The 427 didn’t just win races. It changed Ford’s entire approach to building engines. It taught them where the weak points were, what it took to make an iron block survive high loads, and how to design oiling systems that wouldn’t give up when the pressure was on, literally.

The Engineering Legacy

When Ford engineers started designing the 385-series big blocks that replaced the FE family in 1968, they brought every hard-earned lesson from the 427 with them.

The FE had a 4.63-inch bore spacing, which was fine for 390s and 428s, but it limited how far you could push displacement. The new 385-series used a wider 4.90-inch bore spacing, giving more room for thicker cylinder walls and larger bores without sacrificing cooling. That’s how Ford got engines like the 429 and 460, which shared much of the 427’s philosophy but were easier to cast, easier to maintain, and even tougher.

They also took what they learned from the 427’s oiling system. The 385-series engines went back to a top-fed layout, but they strengthened the main webs, widened the oil passages, and improved pump volume to prevent starvation under load. The oiling “problem” that started this whole revolution was permanently solved in the next generation.

The deep-skirt block design carried over, giving the 429 and 460 that same rock-solid bottom end feel. Even though they didn’t use cross-bolted mains, the webbing was thick enough that the crank sat in a structure just as strong. The result was a big block that could take anything you threw at it… hauling, towing, or screaming down a drag strip.

And while the 427’s racing program was all about pushing the limits, the 385-series engines were about applying those lessons to real-world performance. You could run them hard in a truck, day after day, and they just wouldn’t die.

From Le Mans to the Work Truck

There’s a direct line between the GT40s that tore up Le Mans and the Bullnose Fords that pulled horse trailers and campers two decades later. It sounds like a stretch until you look at what really mattered: durability under stress.

The 427 proved that you could make a high-compression, high-output V8 live at full throttle for 24 hours. Once Ford had that formula, applying it to trucks was easy. Sure, the 460 wasn’t spinning 7,000 RPM, but it still had to handle heavy loads, steep grades, and long hauls in hot weather. That’s the same kind of stress that kills engines when oiling or cooling is marginal.

That’s why those big-block Fords earned their reputation for reliability. They came from an era when Ford had something to prove and wasn’t afraid to overbuild. The 427’s success gave Ford confidence, and the budget, to keep that mindset alive.

When you fire up a Bullnose with a 460 under the hood, you’re hearing the same design philosophy that took Ford to the top of the racing world: build it tough, feed it well, and let it breathe.

A Cultural Shift Inside Ford

Before the 427, Ford was seen as dependable but conservative. They were the company that built your dad’s work truck and your grandma’s grocery-getter. After the 427? Whole different story.

Winning Le Mans changed the brand’s identity overnight. Ford became a performance company. That victory opened the door for the Cobra Jet, the Boss 429, and even the Thunder Jet engines that filled muscle cars through the late ’60s and early ’70s. The 427’s DNA ran through all of them.

That same culture of durability and pride carried into the trucks of the late ’70s and ’80s. The Bullnose generation wasn’t designed to win races, but it was built with that same Ford attitude. Solid, practical, a little overbuilt, and proud of it. When you look at the engineering on those trucks, from the frames to the drivetrains, it’s the same thinking that made the 427 such a success: do it right, even if it takes longer.

A Legacy Measured in Iron

For enthusiasts, the 427 Side Oiler is more than just an engine. It’s proof of what happens when a company gets serious about performance and refuses to accept second place. It turned Ford from an also-ran into a powerhouse. And it made possible every tough, torque-heavy big block that came after.

So yeah, your Bullnose F-150 never had a 427, but every time you start it, you’re hearing echoes of that engine. The smooth idle, the deep tone, the feeling that the motor could pull a house down… all of it traces back to lessons learned when Ford went to war with Ferrari.

Without the 427, there’s no 429.

Without the 429, there’s no 460.

And without the 460, the Bullnose doesn’t get its reputation for being a hard-pulling, long-living workhorse.

That’s why the 427 matters. It wasn’t just a racing engine. It was a proof of concept that forever changed how Ford built power.

Would You Swap a 427 Side Oiler Into a Bullnose?

Now, this is Bullnose Garage, so let’s ask the question that’s been itching at the back of your mind since the start: “Would it be possible to drop a 427 Side Oiler into a Bullnose Ford?”

Short answer: yes.

Long answer: yes, but your wallet’s going to need CPR.

The swap can be done. The Bullnose engine bay is plenty roomy, the frame can take it, and adapter kits exist to bolt almost anything to almost anything. But just because you can doesn’t mean you should.

The Money Problem

A real, documented 427 Side Oiler block is one of the most expensive pieces of Ford iron on the planet. These weren’t mass-produced like 390s or 428s. Depending on the condition, just the block alone can cost anywhere from $10,000 to $20,000, and that’s before you’ve bought heads, crank, rods, pistons, or an intake.

If you’re lucky enough to find a complete running engine, (talking a real one here, not a service replacement or re-stamped block), you’re probably looking at $30,000 to $40,000, minimum. That’s more than most Bullnose trucks are worth fully restored.

And that’s just to own one. If you plan to actually drive it, you’ll want a modern oiling system, better cooling, and upgraded ignition. The Side Oiler was designed to live at wide-open throttle, not to idle in traffic on a summer day with the A/C blowing. It’ll do it, but it’ll complain the whole time.

The Practicality Problem

Even if money isn’t an issue, there’s the matter of weight and geometry. The FE family isn’t exactly light. A fully dressed 427 tips the scales at roughly 620 to 650 pounds, and that’s all iron. No aluminum block, no fancy alloys. Your front suspension would notice that extra hundred pounds compared to a Windsor or even a 460.

Then there’s the intake. Because the FE’s intake manifold forms part of the cylinder heads, it’s a monster, sometimes 70 pounds by itself. Swapping one of those isn’t a “pop it off before lunch” kind of job. You’ll want a hoist, or at least a few strong friends and a six-pack.

As for transmission fitment, you’d need FE-to-modern bellhousing adapters, and custom headers would almost be mandatory. You could get creative with mounts and driveshaft angles, but the swap would involve plenty of cutting, welding, and head-scratching. Nothing impossible, just not easy.

And don’t forget about the fuel system. The 427’s thirst makes a 460 look efficient. On a good day, you might see 5 to 7 miles per gallon and that’s if you’re nice to it. But let’s be honest, nobody puts a Side Oiler in a truck to hypermile.

The Cool Factor

Here’s where logic goes out the window. Because a Bullnose with a 427 under the hood isn’t about practicality, it’s about bragging rights. It’s the kind of swap that makes people stop mid-sentence at a car show.

Most folks expect to see a Windsor or maybe a 460 if they peek under the hood. But when they spot those wide FE valve covers and that distinctive side gallery bulge on the block? Game over. You’ve just won every “coolest swap” conversation within a 500-foot radius.

It’s ridiculous. It’s expensive. It’s completely unnecessary. And it’s also one of the most badass things you could ever do to a Bullnose. The kind of thing that makes people say, “You did what?” and then immediately grab their phones for a picture.

The Reality Check

For most people, it just doesn’t make sense. Real 427 Side Oilers are collector pieces now, and every one that gets pulled out of a crate or race car to be stuffed into a pickup is one less surviving piece of Ford racing history.

If you want the look and the power without the museum-level price tag, a 390 or 428 FE build will get you most of the way there. Those engines share the same basic architecture and can be built to run hard with modern internals. You’ll still get that FE sound and torque curve, but without needing a second mortgage.

Or, if you’re chasing performance, a well-built 460 or even a stroked 408 Windsor will out-torque a stock 427 and cost a fraction of the price. You’ll have parts support, lighter weight, and fewer headaches.

But if you do happen to find a dusty Side Oiler sitting in your uncle’s barn and decide to make it happen? You’ll have my respect forever. Because a Bullnose with a 427 Side Oiler under the hood isn’t a build — it’s a statement.

It says: “Yeah, I put a Le Mans engine in my farm truck. What are you gonna do about it?”

The Wrap-Up: Ford’s Iron-Fisted Masterpiece

The Ford 427 Side Oiler wasn’t built to be practical. It wasn’t built to idle smooth, sip gas, or pass emissions. It was built for one reason: to win. To take the fight to Chrysler at Daytona, to humiliate Ferrari at Le Mans, and to prove that American engineering could go toe-to-toe with anyone on earth.

And it did.

It gave Ford four straight Le Mans victories, a NASCAR championship run, and a fearsome reputation on the drag strip that still echoes in the pits today. This engine didn’t just make power… it made history. Every FE that came before it led to it, and every Ford big block that came after owed it a debt.

The FE Family’s Final Triumph

The 427 Side Oiler was the pinnacle of the FE family. It took a design that started life in the late 1950s and refined it into something worthy of global domination. From the deep-skirt block to the cross-bolted mains and the side-mounted oil gallery, every inch of that engine was purpose-built to solve problems most manufacturers didn’t even know they had yet.

It proved that Ford could do more than build reliable engines, they could build bulletproof ones. The same DNA that made the 427 survive Le Mans for 24 hours without coughing up its crankshaft eventually found its way into the 429 and 460. Those engines powered dump trucks, tow rigs, RVs, and the heavy-duty Bullnose pickups that became legends in their own right.

Lessons That Lasted

The real genius of the 427 wasn’t just its raw output. It was what Ford learned from it. They learned how to strengthen block castings, balance oil pressure, and keep bearings alive under conditions that would kill most engines. They learned that overbuilding doesn’t just win races. It earns reputations too.

And that mindset filtered down through decades of Ford engineering. When you look at a 460 pulling a trailer through the mountains without breaking a sweat, that’s the 427’s legacy at work. When you hear a Bullnose rumble to life and feel that deep torque right off idle, you’re feeling the echoes of a time when Ford refused to cut corners.

The Soul of a Winner

For us truck guys, the 427 isn’t just a piece of racing trivia. It’s proof that Ford earned its stripes. It’s the reason we can still brag that our trucks were built tough before “Built Ford Tough” was even a slogan.

Every Bullnose out there, from the humble 300 straight-six to the big 460, carries that same bloodline. You can trace it straight back to the moment Ford decided they were done playing nice and started building engines to win.

No, your ’85 F-150 never came with a 427 under the hood. But the lessons learned from that engine shaped every big block Ford that followed, and every time you fire yours up, you’re hearing a little piece of Le Mans in the exhaust note.

The 427 Side Oiler wasn’t just an engine. It was a statement — one that said, Ford doesn’t follow. Ford fights.

And that fight lives on in every truck still rolling down the road today.

If you want more specific information on Bullnose Ford Trucks, check out my YouTube Channel!

For more information on Bullnose Fords, you can check out the BullnoseFord SubReddit or Gary’s Garagemahal. Both are excellent resources.

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. If you see an Amazon link on my site, purchasing the item from Amazon using that link helps out the Channel.